By: Sagal Abdigani

We are Americans who were treated like criminals by our own government for no good reason.

In 1991, I fled my home in Somalia to escape the civil war there. After nine years of living in uncertainty as a refugee in Yemen, I won a lottery to immigrate to America. I couldn’t believe my luck. I couldn’t stop smiling.

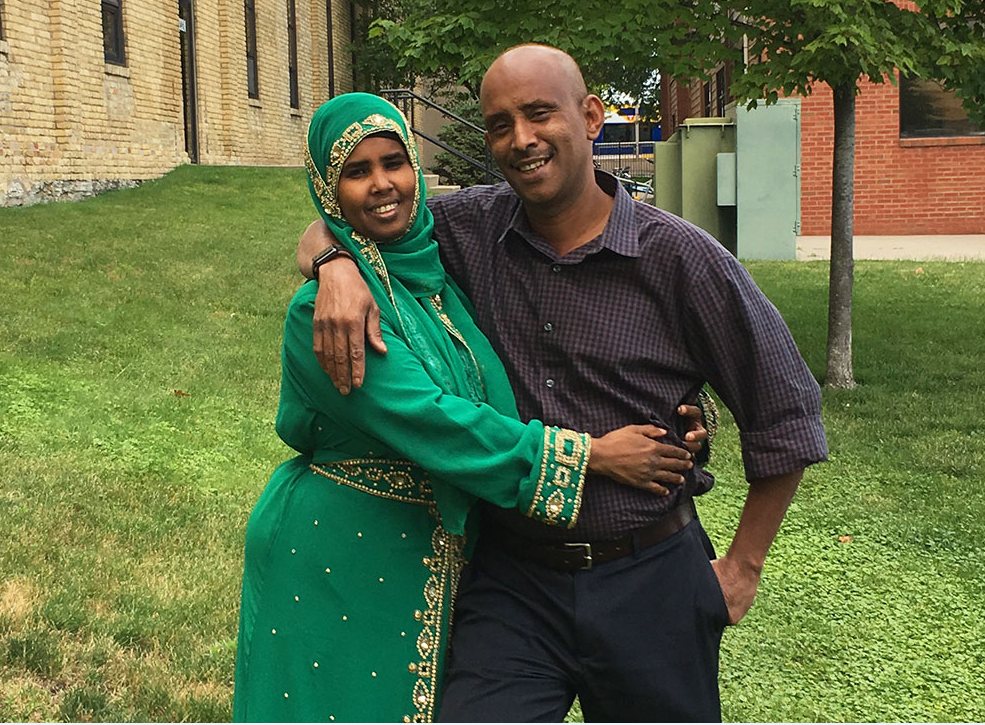

It was confusing in the beginning. I didn’t understand English or basic customs, but I adapted pretty quickly to life in my new country. It was here that I met my husband Abdi, a fellow Somali immigrant. We have four wonderful children, ages 7, 8, 10, and 16. They love school, soccer, and video games. They have never known any other home.

The day I became a citizen in 2009 was one of the proudest days of my life. Still, it’s hard to be away from everyone I left behind. Being able to see my sisters who live closer — one in Canada and the other in Maine — connects me to my family and brings me great comfort.

But recently, my family went through something terrible at the border while coming back home to America from Canada. I no longer feel the safety and security I thought I had found in my new home. My children are traumatized and we are all too scared to travel again.

In March 2015, we were coming back from a visit to Saskatchewan to see my sister and her family. When we got to the border to cross into North Dakota, officers suddenly surrounded our minivan and pointed guns at the entire family. My children, who had been sleeping, woke up and started screaming, afraid we would be killed. The border officers took my husband away in handcuffs in front of my children, who were sobbing.

We didn’t know where they took Abdi, and they wouldn’t tell us. We didn’t know if we’d ever see him again. They took the rest of us to another room. I asked if I could take my children home and come back for my husband or if a family member could come take the children. “No. You’re all the same,” they said to us. “You’re all detainees, including the children.”

My children were very scared, and there was nothing I could do to soothe them.

“Maybe they’ll kill us after sunset,” my 8-year-old daughter said. I can’t forget these words. For hours, the guards wouldn’t give us anything except for a bit of candy, even though I told them I had real food in the minivan for my kids. After about six hours, they gave the children hamburgers — but nothing for me.

All this time, I had no idea what was happening to my husband, and no one would tell me. I became convinced they had killed him. My phone had been taken away, but my son still had his phone. He gave it to me, and I called 911 to report that we were being held against our will and that we feared for our safety. But a border officer realized what I was doing, grabbed the phone, and spoke to the 911 operator. He must have convinced her not to send anyone because no police came to help us.

Two officers then took my then-14-year-old son to another room, patted him down, and told him to take off his clothes for a strip search. He refused to undress, and they didn’t force him, but he was still very upset by the experience. It still hurts me to think about it.

After more than 10 hours, we were suddenly free to go. Seeing Abdi alive was overwhelming. I learned that his experience was even worse than ours: They had kept him handcuffed without food or water for hours until he passed out, and they had to call an ambulance. Officers questioned him about us, about his work, and about his religion. They wouldn’t let him speak to a lawyer.

When we got back to Minneapolis, we went to our local FBI and Department of Homeland Security offices to report what had happened. We learned that Abdi was on a terrorism “watchlist.” This shocked us because we don’t know why the government would put Abdi on such an awful list — and it won’t tell us. I’ve learned that a million people are on this watchlist, and that the government doesn’t need to have reliable information to put someone on it.

We have filed forms to get Abdi off the list, but we haven’t heard anything back. It seems extremely easy to get on the list based on wrong information — especially if you’re Muslim — and virtually impossible to get off.

Our daily life is generally good. My kids do well in school, and our oldest will be applying to college this year. But I’m too scared to travel now to visit the family I miss. I’m convinced the same thing — or worse — will happen if we try. None of us can get that terrible day out of our minds. My children still have nightmares and are now terrified of police.

My oldest son has started talking about becoming a lawyer to help people who have been harmed like we were. I want to believe that America is a place where justice is possible, and I want him to believe this, too. That’s why my family is suing the government over what happened to us and over my husband’s struggle to clear his name.

I want to go back to believing that my family and I can travel and come home safely, without our own government’s officials harming us.

Read more about the lawsuit the ACLU is filing on behalf of the Wilwal-Abdigani family here.