One cold autumn night, Amanda’s 13-year-old son had an asthma attack that was so severe, he had to be rushed to the hospital in an ambulance. Amanda’s husband rode with their son while Amanda stayed behind to quickly check in with their older boy and ask him to watch the baby. Then with the sound of her baby’s cries trailing behind her, Amanda ran out of the house to follow the ambulance in her car.

On the way to the hospital, blue and red lights appeared in Amanda's rearview mirror. She pulled to the side of the road and rolled her window down to speak with the police officer.

Amanda is an undocumented immigrant. She has lived in Watonwan County for more than 20 years, but Minnesota barred her from getting a driver's license because of her immigration status. The officer gave Amanda a ticket for driving without a license and then informed Amanda that she could not continue driving to the hospital. Instead, she had to sit in her car and wait for someone with a license to pick her up.

Amanda called and woke up her oldest son, who had recently received his driver's license. He got himself ready, called a sitter for the baby, and found his mother on the side of the road 20 minutes later.

"I was crying in my car because my husband was already in the hospital," Amanda said. "I wanted to run to the hospital. I felt those 20 minutes to be eternal."

Amanda's experience of being unable to drive in an emergency was not unusual for undocumented people in Minnesota. In 2003, then Gov. Tim Pawlenty signed an order requiring proof of legal residence to obtain a Minnesota driver's license, which took away undocumented people’s right to drive overnight.

But this didn't stop people from driving.

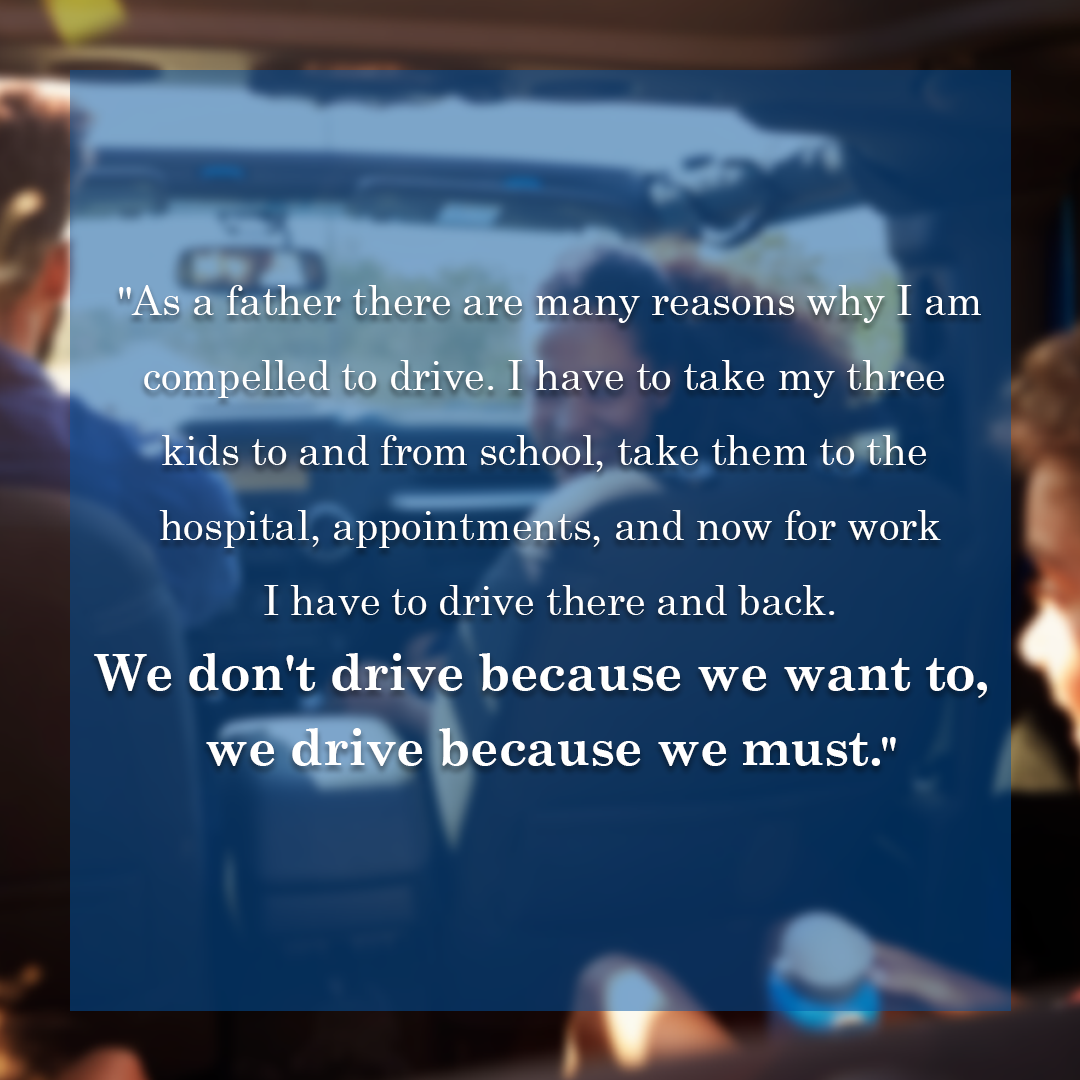

"We don't drive because we want to, we drive because we must," said Nelvin, a resident of Watonwan County. "As a father, there are many reasons why I am compelled to drive. I have to take my three kids to and from school, take them to the hospital, appointments, and now for work I have to drive there and back."

On March 7, Gov. Tim Walz signed the "Driver's Licenses for All" bill into law. With this law, more than 80,000 Minnesotans can now apply for a driver's license no matter their immigration status.

But obtaining a driver's license is still a complicated process for many undocumented Minnesotans. Previous traffic violations and unpaid tickets could obstruct their efforts to get a license. One way that the ACLU-MN has been addressing this challenge is holding legal clinics.

On Sunday, October 15, the ACLU-MN and our partner Convivencia Hispana hosted a legal clinic in the Watonwan County Library in St. James. County residents looked up tickets and traffic violations on their record and worked with a lawyer to write a letter to a county judge, requesting the expungement of convictions and the waiver of outstanding fees and fines.

About 80 families took part in the legal clinic, which cleared about 300 infractions. So many people came seeking help that some had to be turned away when the clinic ended.

The ACLU-MN also is working to ensure that newly licensed drivers know their rights if they are pulled over by police.

“Driver’s licenses for all means that the ACLU of Minnesota is committed to making sure all Minnesotans, regardless of immigration status, have their rights protected,” said ACLU-MN Community Engagement Director Julio Zelaya. “These clinics help us reach people that might not know about their rights and assist them in getting their driver’s licenses. It allows them to do the routine, day-to-day things that all Minnesotans take for granted – drive to the grocery story, bring their kids to school, and watch their children play football or take part in a school play.”

While this legal clinic was vital for dozens of people in Watonwan County, the demand for assistance and information is great throughout the state. Petitioning for expungement happens at the county level. For this reason, legal clinics can only focus on one of Minnesota's 87 counties at a time.

For Amanda, like thousands of other undocumented Minnesotans, a driver’s license means she can travel further from home with tranquility.

Currently, Amanda is working on getting her license so she and her children can have peace of mind when they are going to school, work, and traveling throughout the state. And if there is ever an emergency, Amanda will be able to rush to the hospital without fear of being forced to sit and wait on the side of the road.