Tierre Caldwell grew up with his mom bringing him to the polling station, his feet peeking out from under the polling booth. He planned on doing the same for his children someday.

Yet even though he registers others to vote, he was not allowed to vote himself. Minnesota bars people on felony probation from casting a ballot. The last time Tierre could legally vote, the year was 2008.

His children asked him, “Daddy, when are we going with you to vote?” He says it’s hard to encourage your kids to vote when you cannot.

“I’ve already paid my debt to society,” Tierre said. “I’m paying taxes, but I don’t really feel like I’m a part of ‘society’ because I can’t vote. I can’t vote for my kids’ sake for who to put on the school board, I can’t be part of any of that.”

That’s why the ACLU of Minnesota and national ACLU joined together to sue the Minnesota Secretary of State’s Office on Oct. 21 to restore voting rights.

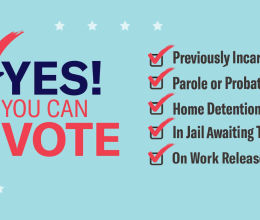

More than 52,000 Minnesotans are barred from voting, even though they live, work, raise families and pay taxes in our communities. The state prohibits them from voting while they’re on felony probation or supervision. That’s true even after they have finished serving any prison term, and even if they’ve never had to spend a day in prison.

They are our neighbors. They live in every county of our state. Yet Minnesota is violating their rights to due process and equal protection under the state Constitution by prohibiting them from choosing who will represent them.

“Voting is the one thing that makes you feel free,” Tierre said. “Statistics show the majority of people who vote don’t go back to prison. It makes me feel like they (the government) can take my tax money, but I can’t participate in selecting our leadership. I have a problem with that.”

The state’s voting ban doesn’t serve any legitimate or rational government interest, said ACLU-MN Staff Attorney David McKinney.

“The criminal justice system is supposed to be about reform, redemption and reintegration into society,” McKinney said. “Denying people the vote flies in the face of these goals while violating a fundamental right.”

Denying the vote hurts people of color and those in Greater Minnesota the most.

“Minnesota has never articulated any justification for disenfranchising citizens who live in our communities following a felony conviction, and none exists,” said Craig Coleman, a partner with Faegre Baker Daniels, pro bono co-counsel on the case.

“The exclusion of these citizens from the political process is fundamentally wrong, undemocratic, and corrosive to constitutional governance.”

VOTING RIGHTS FACTS:

Disenfranchisement disproportionally affects people of color.

- African Americans comprise about 4% of Minnesota’s voting-age population, but they account for more than 20% of these disenfranchised voters living in the community.

- American Indians make up less than 1% of Minnesota’s voting-age population but comprise almost 7% of those disenfranchised.

- Latinx make up less than 2.5% of Minnesota’s voting-age population but comprise almost 6% of those disenfranchised.

Disenfranchisement hits Greater Minnesota the hardest.

- About 70% of those barred from voting live outside Hennepin and Ramsey Counties.

- Probation lengths in Greater Minnesota are on average 46% longer.

Minnesota has one of the nation’s highest rates for people on probation or supervision, which means more people are prohibited from voting.

- In 2016, one in 41 Minnesota adults was on probation or parole, making us the state with the nation’s seventh-highest rate for people on supervision.

The number of offenses considered felonies has exploded in Minnesota, which means more people cannot vote.

- There were less than 100 crimes considered felonies in the mid-1800s. Today, that number is close to 400.

- Many low-level and nonviolent crimes are now classified as felonies.

Barring people from voting while they’re on probation or supervision does not work because it:

- Undermines rehabilitation.

- Increases recidivism.

- Alienates individuals from their communities.

- Fails to achieve any deterrent effect.

Letting people vote while they’re on probation helps people, communities and families because:

- Individuals who vote tend to be more active in their communities.

- Voting connects people to their communities and reduces recidivism.

- Children are more likely to vote as adults if they are raised by parents who vote.

Sources: U.S. Census; the Minnesota Department of Corrections pursuant to a Minnesota Government Data Practices Act request; Minnesota Justice Research Center, “Felon Disenfranchisement in Minnesota,” Feb. 21, 2019; Pew Charitable Trusts, Probation and Parole Systems Marked by High Stakes, Missed Opportunities, Sept. 2018; Mark Haase, Civil Death in Modern Times: Reconsidering Felony Disenfranchisement in Minnesota, Minnesota Law Review, Sept. 1, 2015; Minn. Sentencing Guidelines and Commentary 96-123 (Aug. 1, 2014); and Minnesota Statutes.